vague

archive

APOTHEOSIS

24.10.2025 • 12:18

Vienna

APOTHEOSIS

24.10.2025 • 12:18

Vienna

12.10.2025 • 15:37

Vienna

12.10.2025 • 15:37

Vienna

Nature and Space (From the book "Seeing Like a State" by James C. Scott)

Monocultures are, as a rule, more fragile and hence more vulnerable to the stress of disease and weather than polycultures are. Any unmanaged forest may experience stress from storms, disease, drought, fragile soil, or severe cold. A diverse, complex forest, however, with its many species of trees, its full complement of birds, insects, and mammals, is far more resilient – far more able to withstand and recover from such injuries – than pure stands.

12.10.2025 • 15:34

Vienna

Nature and Space (From the book "Seeing Like a State" by James C. Scott)

Monocultures are, as a rule, more fragile and hence more vulnerable to the stress of disease and weather than polycultures are. Any unmanaged forest may experience stress from storms, disease, drought, fragile soil, or severe cold. A diverse, complex forest, however, with its many species of trees, its full complement of birds, insects, and mammals, is far more resilient – far more able to withstand and recover from such injuries – than pure stands.

12.10.2025 • 15:34

Vienna

sound of the month

26.09.2025 • 17:18

Vienna

sound of the month

26.09.2025 • 17:18

Vienna

at what point does digital architecture become the architecture itself?

10.09.2025 • 17:29

Kazanlak

at what point does digital architecture become the architecture itself?

10.09.2025 • 17:29

Kazanlak

i can die peacefully now

02.08.2025 • 22:30

Barcelona

i can die peacefully now

02.08.2025 • 22:30

Barcelona

"Only the dead have seen the end of war."

– “Soliloquies in England and Later Soliloquies," George Santayana, 1962

31.07.2025 • 18:57

Barcelona

"Only the dead have seen the end of war."

– “Soliloquies in England and Later Soliloquies," George Santayana, 1962

31.07.2025 • 18:57

Barcelona

this is where i post from

20.07.2025 • 00:05

Berlin

this is where i post from

20.07.2025 • 00:05

Berlin

sunday mood

19.07.2025 • 01:09

Berlin

sunday mood

19.07.2025 • 01:09

Berlin

SQUARE ONE

19.07.2025 • 01:07

Berlin

SQUARE ONE

19.07.2025 • 01:07

Berlin

26.05.2025 • 00:45

Vienna

26.05.2025 • 00:45

Vienna

26.05.2025 • 00:38

Vienna

26.05.2025 • 00:38

Vienna

Hyperconnection vs. connection – notes on digital life, metro ghosts, and the pleasure of overhearing nonsense

We live in an age where the miracle of the internet has become so deeply embedded in our lives that it feels less like a tool and more like the air we breathe. It’s remarkable, really—within seconds we can summon any piece of recorded music ever made, download entire libraries into our pockets, or initiate conversations with strangers across the world. The world has never been more available. And yet, somehow, less present.

There’s a curious paradox to hyper-digital life. As we become increasingly connected to each other online, we seem to drift further from the texture of reality itself. I noticed this on the metro: rows of people, AirPods in, Instagram open everywhere, bodies present but senses elsewhere. We’ve outsourced our eyes and ears to curated feeds and algorithmic playlists.

In theory, we’re expanding our awareness. In practice, we’re filtering out everything that doesn’t come with a “like” button. We scroll to see what people think, but not the people right next to us. This is much more noticeable in a big city with over a million residents because the isolation and segregation of society there is much stronger than in smaller towns. Everyone is together, but no one is really here.

I’m not here to moralize. I love my tech. But sometimes I like to disconnect—not in a “wellness retreat” kind of way, but in a “just listening to strangers argue about bananas” kind of way. Eavesdropping, it turns out, is oddly therapeutic. It reminds me that most people are beautifully, hilariously irrational. And that in this world of avatars and endless opinions, the most grounding thing might just be the banality of someone else's real, unfiltered life.

There’s comfort in remembering that people around us aren’t background NPCs. They’re real. And so are we.

13.04.2025 • 23:22

Vienna

Hyperconnection vs. connection – notes on digital life, metro ghosts, and the pleasure of overhearing nonsense

We live in an age where the miracle of the internet has become so deeply embedded in our lives that it feels less like a tool and more like the air we breathe. It’s remarkable, really—within seconds we can summon any piece of recorded music ever made, download entire libraries into our pockets, or initiate conversations with strangers across the world. The world has never been more available. And yet, somehow, less present.

There’s a curious paradox to hyper-digital life. As we become increasingly connected to each other online, we seem to drift further from the texture of reality itself. I noticed this on the metro: rows of people, AirPods in, Instagram open everywhere, bodies present but senses elsewhere. We’ve outsourced our eyes and ears to curated feeds and algorithmic playlists.

In theory, we’re expanding our awareness. In practice, we’re filtering out everything that doesn’t come with a “like” button. We scroll to see what people think, but not the people right next to us. This is much more noticeable in a big city with over a million residents because the isolation and segregation of society there is much stronger than in smaller towns. Everyone is together, but no one is really here.

I’m not here to moralize. I love my tech. But sometimes I like to disconnect—not in a “wellness retreat” kind of way, but in a “just listening to strangers argue about bananas” kind of way. Eavesdropping, it turns out, is oddly therapeutic. It reminds me that most people are beautifully, hilariously irrational. And that in this world of avatars and endless opinions, the most grounding thing might just be the banality of someone else's real, unfiltered life.

There’s comfort in remembering that people around us aren’t background NPCs. They’re real. And so are we.

13.04.2025 • 23:22

Vienna

13.04.2025 • 13:02

Vienna

13.04.2025 • 13:02

Vienna

i love this building

31.03.2025 • 01:30

Vienna

i love this building

31.03.2025 • 01:30

Vienna

24.03.2025 • 23:47

Vienna

24.03.2025 • 23:47

Vienna

24.03.2025 • 23:46

Vienna

24.03.2025 • 23:46

Vienna

17.03.2025 • 00:15

Vienna

17.03.2025 • 00:15

Vienna

2020 I was making books where were you at ?

17.03.2025 • 00:13

Vienna

2020 I was making books where were you at ?

17.03.2025 • 00:13

Vienna

01.03.2025 • 17:46

Vienna

01.03.2025 • 17:46

Vienna

usually not a fan of Gaudí's style but this plan is so beautiful

27.02.2025 • 23:07

Vienna

usually not a fan of Gaudí's style but this plan is so beautiful

27.02.2025 • 23:07

Vienna

08.02.2025 • 22:04

Vienna

08.02.2025 • 22:04

Vienna

TRANSLATOR OF THE ZEITGEIST

"the most valuable person today might be the person who deeply groks both product potential & the human environment around it—culture, market signals, user psychology. ai can handle technical coordination & execution mechanics, but it won’t yet read the room like a human who’s lived through trends, upheavals, & niche subcultures." – signüll on X

08.02.2025 • 01:20

Vienna

TRANSLATOR OF THE ZEITGEIST

"the most valuable person today might be the person who deeply groks both product potential & the human environment around it—culture, market signals, user psychology. ai can handle technical coordination & execution mechanics, but it won’t yet read the room like a human who’s lived through trends, upheavals, & niche subcultures." – signüll on X

08.02.2025 • 01:20

Vienna

08.02.2025 • 01:06

Vienna

08.02.2025 • 01:06

Vienna

Beyond the symbols (from the book "Thinking Architecture" by Peter Zumthor)

"Anything goes," say the doers. "Mainstreet is almost all right," says Venturi, the architect. "Nothing works any more," say those who suffer from the hostility of our day and age. These statements stand for contradictory opinions, if not for contradictory facts. We get used to living with contradictions and there are several reasons for this: traditions crumble, and with them cultural identities. No one seems really to understand and control the dynamics developed by economics and politics. Everything merges into everything else, and mass communication creates an artificial world of signs. Arbitrariness prevails. Postmodern life could be described as a state in which everything beyond our own personal biography seems vague, blurred, and somehow unreal. The world is full of signs and information, which stand for things that no one fully understands because they, too, turn out to be mere signs for other things. The real thing remains hidden. No one ever gets to see it.

Nevertheless, I am convinced that real things do exist, however endangered they may be. There are earth and water, the light of the sun, landscapes and vegetation; and there are objects, made by man. such as machines, tools or musical instruments, which are what they are, which are not mere vehicles for an artistic message, whose presence is self-evident.

When we look at objects or buildings which seem to be at peace within themselves, our perception becomes calm and dulled. The objects we perceive have no message for us, they are simply there. Our perceptive faculties grow quiet, unprejudiced and unacquisi-tive. They reach beyond signs and symbols, they are open, empty. It is as if we could see something on which we cannot focus our consciousness. Here, in this perceptual vacuum, a memory may surface, a memory which seems to issue from the depths of time. Now, our observation of the object embraces a presentiment of the world in all its wholeness, because there is nothing that cannot be understood.

There is a power in the ordinary things of everyday life, Edward Hopper's paintings seem to say. We only have to look at them long enough to see it.

08.11.2024 • 22:33

Vienna

Beyond the symbols (from the book "Thinking Architecture" by Peter Zumthor)

"Anything goes," say the doers. "Mainstreet is almost all right," says Venturi, the architect. "Nothing works any more," say those who suffer from the hostility of our day and age. These statements stand for contradictory opinions, if not for contradictory facts. We get used to living with contradictions and there are several reasons for this: traditions crumble, and with them cultural identities. No one seems really to understand and control the dynamics developed by economics and politics. Everything merges into everything else, and mass communication creates an artificial world of signs. Arbitrariness prevails. Postmodern life could be described as a state in which everything beyond our own personal biography seems vague, blurred, and somehow unreal. The world is full of signs and information, which stand for things that no one fully understands because they, too, turn out to be mere signs for other things. The real thing remains hidden. No one ever gets to see it.

Nevertheless, I am convinced that real things do exist, however endangered they may be. There are earth and water, the light of the sun, landscapes and vegetation; and there are objects, made by man. such as machines, tools or musical instruments, which are what they are, which are not mere vehicles for an artistic message, whose presence is self-evident.

When we look at objects or buildings which seem to be at peace within themselves, our perception becomes calm and dulled. The objects we perceive have no message for us, they are simply there. Our perceptive faculties grow quiet, unprejudiced and unacquisi-tive. They reach beyond signs and symbols, they are open, empty. It is as if we could see something on which we cannot focus our consciousness. Here, in this perceptual vacuum, a memory may surface, a memory which seems to issue from the depths of time. Now, our observation of the object embraces a presentiment of the world in all its wholeness, because there is nothing that cannot be understood.

There is a power in the ordinary things of everyday life, Edward Hopper's paintings seem to say. We only have to look at them long enough to see it.

08.11.2024 • 22:33

Vienna

17.12.2024 • 11:27

Berlin

17.12.2024 • 11:27

Berlin

16.12.2024 • 14:35

Berlin

16.12.2024 • 14:35

Berlin

16.12.2024 • 14:32

Berlin

16.12.2024 • 14:32

Berlin

a building representing the religion

Why, in the name of a religion that promotes modest and simple living, are there buildings with gilded domes, hand-painted murals with gem stones and the people running them drive S-classes?

02.12.2024 • 01:50

Vienna

a building representing the religion

Why, in the name of a religion that promotes modest and simple living, are there buildings with gilded domes, hand-painted murals with gem stones and the people running them drive S-classes?

02.12.2024 • 01:50

Vienna

don't hide from your roots

02.12.2024 • 01:32

Vienna

don't hide from your roots

02.12.2024 • 01:32

Vienna

20.11.2024 • 21:19

Vienna

20.11.2024 • 21:19

Vienna

14.11.2024 • 00:04

Vienna

14.11.2024 • 00:04

Vienna

14.11.2024 • 00:01

Vienna

14.11.2024 • 00:01

Vienna

12.11.2024 • 00:35

Vienna

12.11.2024 • 00:35

Vienna

Drowning in Information While Starving for Wisdom (from the book "Lo—TEK" by Julia Watson)

From the Greek mythos, meaning story-of-the-people, mythology has guided mankind for millennia. Three hundred years ago, intellectuals of the European Enlightenment constructed a mythology of technology. Influenced by a confluence of humanism, colonialism, and racism, the mythology ignored local wisdom and indigenous innovation, deeming it primitive. Guiding this was a perception of technology that feasted on the felling of forests and extraction of resources. The mythology that powered the Age of Industrialization distanced itself from natural systems, favoring fuel by fire.

Today, the legacy of this mythology haunts us. Progress at the expense of the planet birthed the epoch of the Anthropocene—our current geological period characterized by the undeniable impact of humans upon the environment at the scale of the Earth. Charles Darwin, scholar and naturalist who is seen as the father of evolutionary theory, said "extinction happens slowly," yet sixty percent of the world's biodiversity has vanished in the past forty years." Coming to terms with an uncertain future and confronted by climate events that cannot be predicted, species extinctions that cannot be arrested, and ecosystem failures that cannot be stopped, humanity is tasked with developing solutions to protect the wilderness that remains, and transform the civilizations we construct. While we are drowning in this Age of Information, we are starving for wisdom.

08.11.2024 • 22:33

Vienna

Drowning in Information While Starving for Wisdom (from the book "Lo—TEK" by Julia Watson)

From the Greek mythos, meaning story-of-the-people, mythology has guided mankind for millennia. Three hundred years ago, intellectuals of the European Enlightenment constructed a mythology of technology. Influenced by a confluence of humanism, colonialism, and racism, the mythology ignored local wisdom and indigenous innovation, deeming it primitive. Guiding this was a perception of technology that feasted on the felling of forests and extraction of resources. The mythology that powered the Age of Industrialization distanced itself from natural systems, favoring fuel by fire.

Today, the legacy of this mythology haunts us. Progress at the expense of the planet birthed the epoch of the Anthropocene—our current geological period characterized by the undeniable impact of humans upon the environment at the scale of the Earth. Charles Darwin, scholar and naturalist who is seen as the father of evolutionary theory, said "extinction happens slowly," yet sixty percent of the world's biodiversity has vanished in the past forty years." Coming to terms with an uncertain future and confronted by climate events that cannot be predicted, species extinctions that cannot be arrested, and ecosystem failures that cannot be stopped, humanity is tasked with developing solutions to protect the wilderness that remains, and transform the civilizations we construct. While we are drowning in this Age of Information, we are starving for wisdom.

08.11.2024 • 22:33

Vienna

On the topic of preservation and destruction

07.11.2024 • 21:57

Vienna

On the topic of preservation and destruction

07.11.2024 • 21:57

Vienna

here for the weekend

31.10.2024 • 00:14

Vienna

here for the weekend

31.10.2024 • 00:14

Vienna

concrete jungle

31.10.2024 • 00:04

Vienna

concrete jungle

31.10.2024 • 00:04

Vienna

city

31.10.2024 • 00:03

Vienna

city

31.10.2024 • 00:03

Vienna

the center of everything

27.10.2024 • 23:56

Vienna

the center of everything

27.10.2024 • 23:56

Vienna

The Fruit Of Knowledge

“But the Hebrew word, the word timshel—‘Thou mayest’— that gives a choice. It might be the most important word in the world. That says the way is open. That throws it right back on a man. For if ‘Thou mayest’—it is also true that ‘Thou mayest not.”

28.10.2024 • 01:08

Vienna

The Fruit Of Knowledge

“But the Hebrew word, the word timshel—‘Thou mayest’— that gives a choice. It might be the most important word in the world. That says the way is open. That throws it right back on a man. For if ‘Thou mayest’—it is also true that ‘Thou mayest not.”

28.10.2024 • 01:08

Vienna

you can do it too

27.10.2024 • 23:56

Vienna

you can do it too

27.10.2024 • 23:56

Vienna

in search of space

It's a natural human desire to overcomplicate simple things as much as possible so that we have the feeling of advancement. I like to call this phenomenon "ovecomplicatism".

26.10.2024 • 23:44

Vienna

in search of space

It's a natural human desire to overcomplicate simple things as much as possible so that we have the feeling of advancement. I like to call this phenomenon "ovecomplicatism".

26.10.2024 • 23:44

Vienna

THERE IS A CERTAIN BEAUTY IN EPHEMERALITY

what is home without sun ?

26.10.2024 • 23:33

Vienna

THERE IS A CERTAIN BEAUTY IN EPHEMERALITY

what is home without sun ?

26.10.2024 • 23:33

Vienna

EVERYTHING IS BRANDED

if you're not gonna leave a trace, why even live?

25.10.2024 • 18:41

Vienna

EVERYTHING IS BRANDED

if you're not gonna leave a trace, why even live?

25.10.2024 • 18:41

Vienna

25.10.2024 • 18:05

Vienna

25.10.2024 • 18:05

Vienna

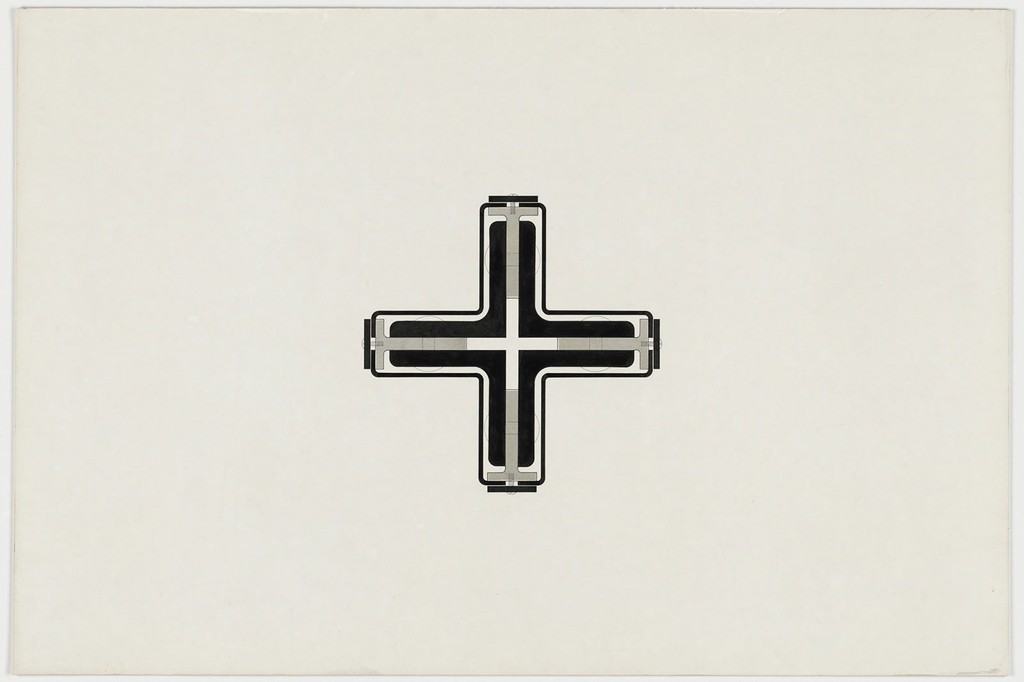

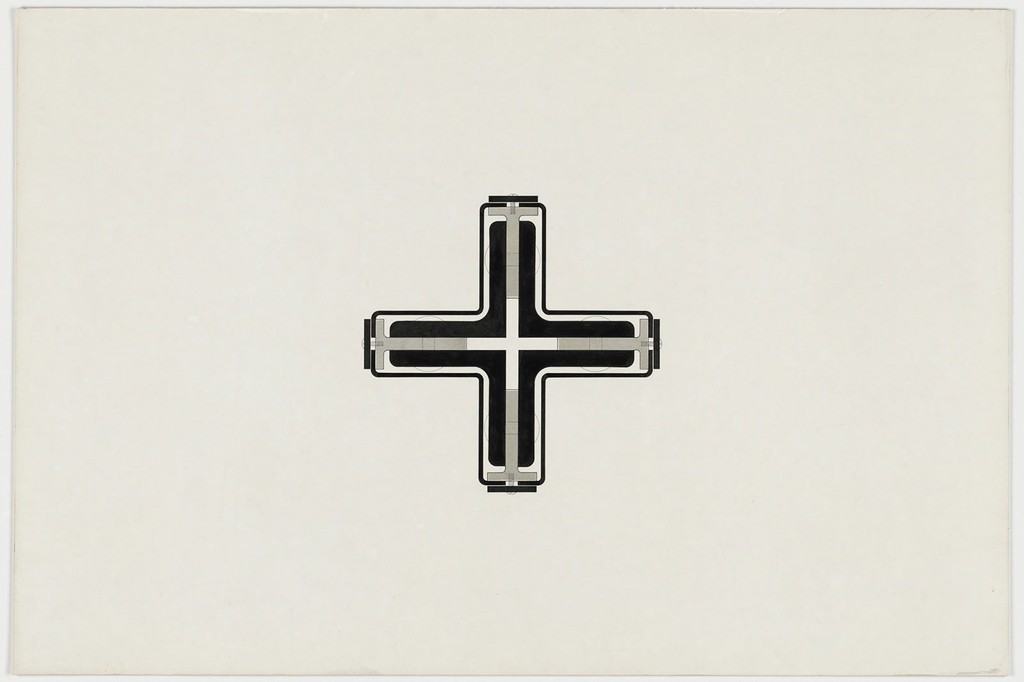

screenshot this work from a lecture once. tried searching for it on google images but i couldn't find who the author is. i guess this makes it even more special now. might hang it on my wall someday

25.10.2024 • 17:55

Vienna

screenshot this work from a lecture once. tried searching for it on google images but i couldn't find who the author is. i guess this makes it even more special now. might hang it on my wall someday

25.10.2024 • 17:55

Vienna

25.10.2024 • 17:31

Vienna

25.10.2024 • 17:31

Vienna

OFFLINE

One of the few places without wars

25.10.2024 • 17:23

Vienna

OFFLINE

One of the few places without wars

25.10.2024 • 17:23

Vienna

STATE OF MIND

curtain wall without bauhaus

25.10.2024 • 02:52

Vienna

STATE OF MIND

curtain wall without bauhaus

25.10.2024 • 02:52

Vienna

INCEPTION

25.10.2024 • 02:42

Vienna

INCEPTION

25.10.2024 • 02:42

Vienna

vague.

The Vague Archive® was created by Hristian Vaglyarov as an exploration archive for research, projects, memories, experiences, information and emotions. This archive features design, architecture, fashion, philosophy, art and much more. Social media is biased, centralised and in most cases detrimental to clear thinking—own your media, your pictures and your right to share whatever you like. 2024 © Vague Archive™ by Hristian Vaglyarov